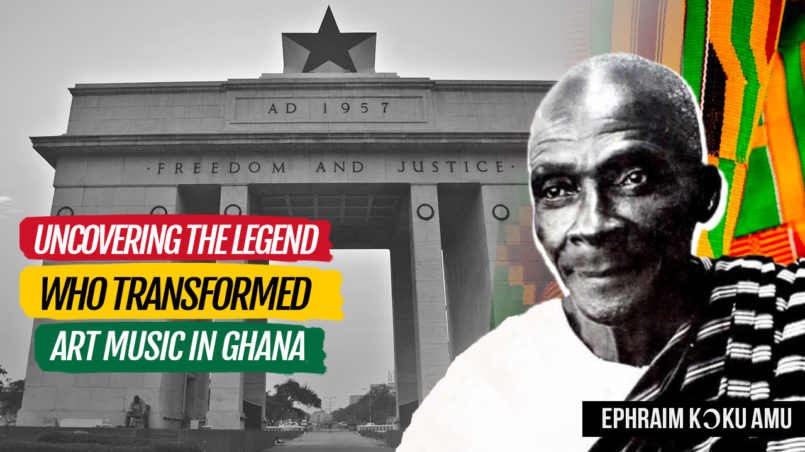

“There is no single individual who has influenced the course of the development of art music in contemporary Ghana as much as Dr. Ephraim Amu.” ~Professor Joseph Handson Kwabena Nketia

Ephraim Kɔku Amu was a Ghanaian musicologist, composer, and teacher. He was born on September 13, 1899, in Peki-Avetile, in the Volta Region of present-day Ghana. His formal education begun at Bremen Mission School in Peki-Avetile in 1906 and later continued at the Middle School in Peki-Blengo in 1912.

He was taught to play the harmonium by the late Theodore Ntem when he attended the Presbyterian Seminary at Abetifi where he was trained as a teacher and catechist. On completion of his training, he was appointed to the staff of the Middle School in Peki-Blengo in 1920. He continued his own musical studies by taking lessons in harmony with the late Reverend J.E. Allotey-Pappoe. He taught music at Blengo Middle School for six years until he was transferred to the Scottish Mission Teacher Training College, now known as the Presbyterian College of Education, Akropong in 1926.

With his deep interest in arts and culture, the seminary became an ideal place for him to interact and work with students. Apart from teaching music he also taught the Ewe language and agriculture. He was also given the role of a housemaster of the school.

Amu began studying the melodies, rhythms, and cadences of Ghanaian traditional songs. He led the Akropong Songs Band in choral musical performances. His research focused on indigenous knowledge such as proverbs, wise sayings, and myths. He emphasized the importance of drum language and other musical forms. He composed several musical pieces in both Ewe, his native language, and Twi.

His notable compositions include “Asԑm yi di ka”, “Mawɔ dɔ na Yesu”, “Adawura bɔ me”, “Israel Hene”, “Onipa da wo ho so”, “Yɛn ara asase ni” among others.”Yɛn ara asase ni,” his most famous work, is a patriotic song that sparked nationalism. It was widely sung at national events and in primary and junior high schools. The title translates to “This Land is Our Own”.

According to Rev. Professor Philip Laryea, a Professor of African Theology, the song was originally composed in 1929 in the Ewe language as “Amewo dzife nyigba” and later translated into Akan, Ga, and Dagbani. (Some also assert the title for the original composition was “Miadenyigbã lɔlɔ̃ la.”)

The translation of the song Yɛn ara asase ni in English reads:

This is our own cherished land, acquired through the blood our Ancestors shed for us.

It is now our turn to continue what our ancestors started.

Pride, cheating and selfishness has scarred our character, and diminished our affection for our land.

Whether or not this nation prospers,

Depends on the character of the citizens of the nation.

Bragging of educational achievements, empty boasting, and vain talk is destroying our nation.

Hard work and respect for one another is what we need.

Selflessness and compassion for one another will bring peace and prosperity to our nation.

Whether or not this nation prospers,

Depends on the character of the citizens of the nation.

Indeed this is a touching song!

In 1933 Amu published his first book titled, “Twenty-five African Songs” which was listed on Sheldon Press in London.

As Amu explored African indigenous culture further, his perspective on certain issues began to change. He began to see the conflicts between his traditional African beliefs and the Christian religion. As a catechist, he was expected to give sermons wearing European attire, including a long-sleeved white shirt, suit, tie, and shoes, regardless of Ghana’s tropical climate.

Amu was bothered not only by the discomfort of wearing a woolen jacket in the hot sun, but also by the way Europeans viewed African culture as pagan, primitive, and superstitious. African clothing, customs, music, language, and even names were considered inappropriate and it was forbidden to wear African clothing or sing African songs in church. In response, he began to take pride in all things African, including wearing African clothing and using locally-made products.

One Sunday, Amu decided to give his usual sermon while wearing traditional African clothing. The Presbyterian leadership was taken aback by the behavior exhibited by Amu. He was called to a meeting by the church’s leadership and cautioned that if he continued to act in ways that ran counter to European norms, he would be expelled from the church. Amu refused to give up his beliefs and as a result, was dismissed from the church.

He was immediately embraced by Achimota School, previously known as Prince of Wales College and School, which closely monitored his work, particularly in music composition and research. He taught at Achimota from 1934 to 1936 before pursuing further studies at the Royal College of Music in London.

Upon his return to Ghana, he taught at the Achimota Music School before being transferred to the Kumasi College of Science and Technology. In 1960, he joined the music department at the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana, Legon. During his decade-long tenure at the university, he also focused on creating bamboo flutes such as the odurogyaba, odurogya, and atɛtɛnbɛn.

In 1965, the University of Ghana awarded him the Honorary Doctorate Degree in Music in recognition of his contribution to music in Ghana in the fields of composition, music education and musicology.

In 1969 the School of Music and Drama in Ghana, headed by Amu, was invited by the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in New York to participate in the International University Choral Festival. They performed at the Lincoln Center and various university campuses in the US.

He received another doctorate from the University of Science and Technology in Kumasi in 1971. His image was also featured on Ghana’s 20000 cedi banknote in honor of his nationalism.

Ephraim Amu passed away on January 2nd, 1995 at the age of 96.

He was not only a highly accomplished musician, known for his extensive compositions and unique style in art music but also a proud African nationalist. He held that embracing good elements from other cultures with universal values is acceptable, but it’s crucial to maintain the best of our own.

Despite being recognized with various awards and distinctions, I believe we can further honor this national icon by renaming, for instance, one of the institutions connected with performing arts after him.